Optimizing Cookie Clicker

Like many others, I’ve been staying at home to slow the spread of COVID-19. Also like many others, I’ve been trying to spend my time in quarantine productively. Nobody can work all the time, though, so in between work on my various projects I’ve been playing Cookie Clicker.

Cookie Clicker took the internet by storm a while back. It’s a browser-based game where you click a cookie to bake cookies. You can then spend these cookies on cursors to click for you, grandmas to bake cookies for you, farms to grow cookies, and so on. Cookie Clicker’s a very charming game, and it’s easy to waste hours on it. The genre of incremental games didn’t start with Cookie Clicker, but it certainly popularized it.

These games are primarily about making a number go up; playing well means making that number go up quickly. How many cookies you’re making per second is the best measure of your performance in Cookie Clicker, since how many cookies you have in your bank at the moment varies as you buy buildings and upgrades and save up for the next ones. This raises an obvious question: what’s the best strategy? How can you get your Cookies per Second (or CpS) as high as possible as quickly as possible? If I was going to be scientific about this (and I was), I needed a way to test out different strategies. To do this, I spent some time…

Building a Simulator

This isn’t strictly necessary. It’s theoretically possible to test out strategies in the game itself by manually executing some algorithm whenever a decision needs to be made. However, I want to do something with my time other than play Cookie Clicker, so I decided to make the computer do the work. In other words, I needed to somehow simulate this game. My original plan was to take the game’s source code, strip out everything but the core game logic, and graft the simulator functionality onto that. The game’s source code is more than 13,000 lines long, though. Sifting through all of that would’ve been a nightmare, and a stripped-down simulation would probably perform better, so I reimplemented the core gameplay in Node.js. This is easier than it might sound; the game has a super helpful wiki and the game itself isn’t super complicated. I cut out some mechanics that introduced too much randomness or distracted from buildings and their upgrades:

(Note that, since the simulator can’t click on the cookie, I always start it off with a single Cursor to make up for that.)

Once the set of mechanics was pruned and I had gotten all the buildings and relevant upgrades represented in code (many thanks to Nicole for helping with that), creating the actual simulator was fairly simple. The basic building block is the GameState class that describes possible states the game could be in. GameStates keep track of what buildings and upgrades you have, how many cookies, how long you’ve been playing, and so on:

class GameState {

readonly cookies: number;

readonly buildings: Record<Building, number>;

readonly upgrades: Upgrade[];

readonly timePlaying: number;

// ...

}

Using this information it can also calculate how many cookies you’re producing every second:

class GameState {

// ...

cookiesPerSecond(): number { /* ... */ }

// ...

}

The final piece of the puzzle is that GameStates can handle doing things like waiting or buying buildings:

class GameState {

// ...

buyBuilding(building: Building): GameState { /* ... */ }

buyUpgrade(upgrade: Building): GameState { /* ... */ }

wait(time: number): GameState { /* ... */ }

}

This is everything our simplified Cookie Clicker needs. Note that all of these functions return a new GameState without altering the existing one. GameStates are immutable; you can’t alter their values, only create modified versions. In this case it’s really useful for evaluating potential futures without committing to any of them.

(Side note: While buildings and upgrades are technically different things, they share a lot of important attributes. The player has to spend cookies to get them, and they typically increase CpS by some amount. “Buildings and upgrades” is kind of a mouthful, so let’s use the term item as a catch-all for purchasable things.)

The other important component is the Simulator class. Each Simulator has a strategy it’s testing using the following process:

- Examine all available items.

- Choose one according to your strategy.

- If you can’t afford it, wait until you can.

- Buy it.

- Repeat.

This process repeats until some time limit is reached.

Strategies

Minimize Cost

This strategy always buys the cheapest item available. This makes some degree of sense. Buying items as soon as possible means that your CpS is increasing fairly regularly.

Maximize CpS Increase Per Cookie Spent

This strategy buys the item with the highest value for \(\frac{\Delta \text{CpS}}{\text{Cost}}\). This is also pretty sensible; making sure your purchases are as efficient as possible can’t be a bad thing.

Minimize Payback Period

Payback period is a measurement used by the add-on Cookie Monster. It’s equal to \(\text{Time to Afford} + \frac{\text{Cost}}{\Delta \text{CpS}}\). You can think of it as how long you have to wait to get the item and then how long it takes for said item to pay for itself.

Results

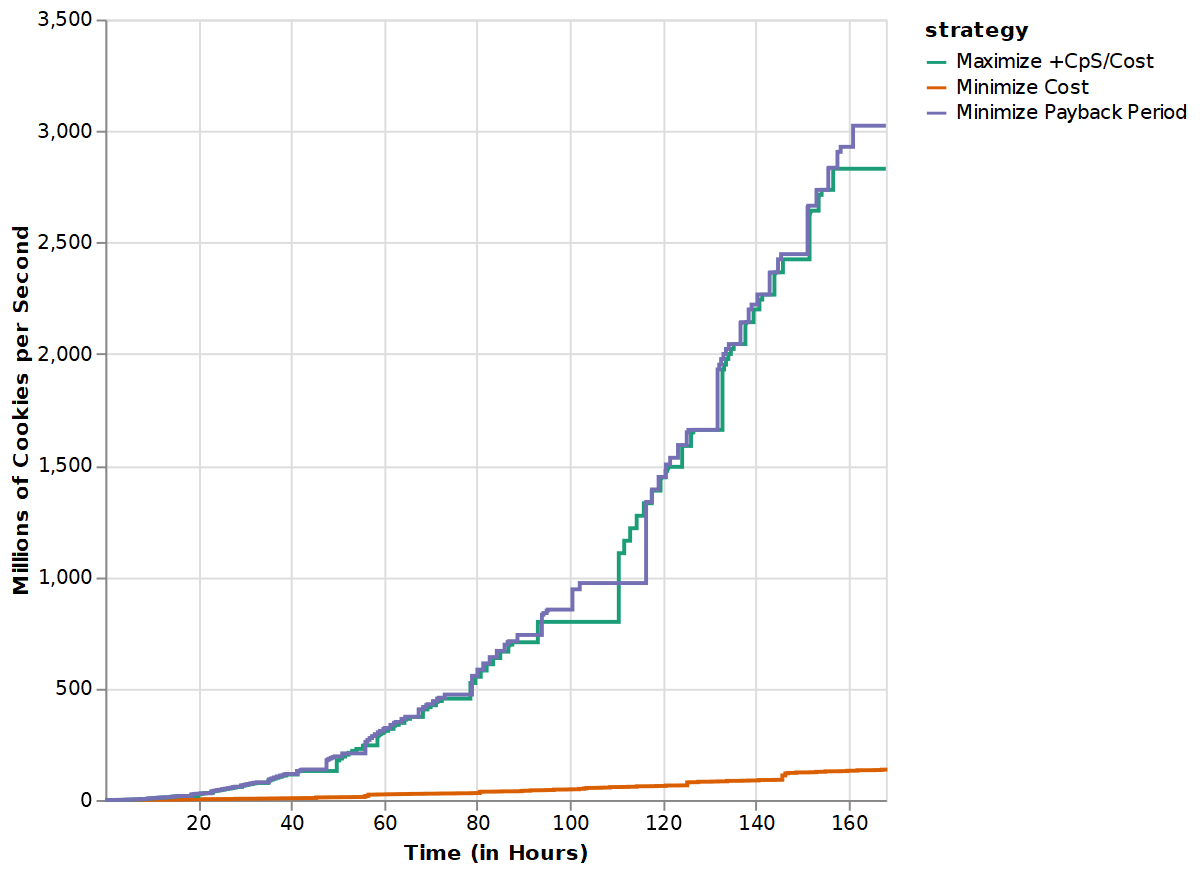

I simulated these strategies over a virtual week and used Vega-Lite to graph the results.

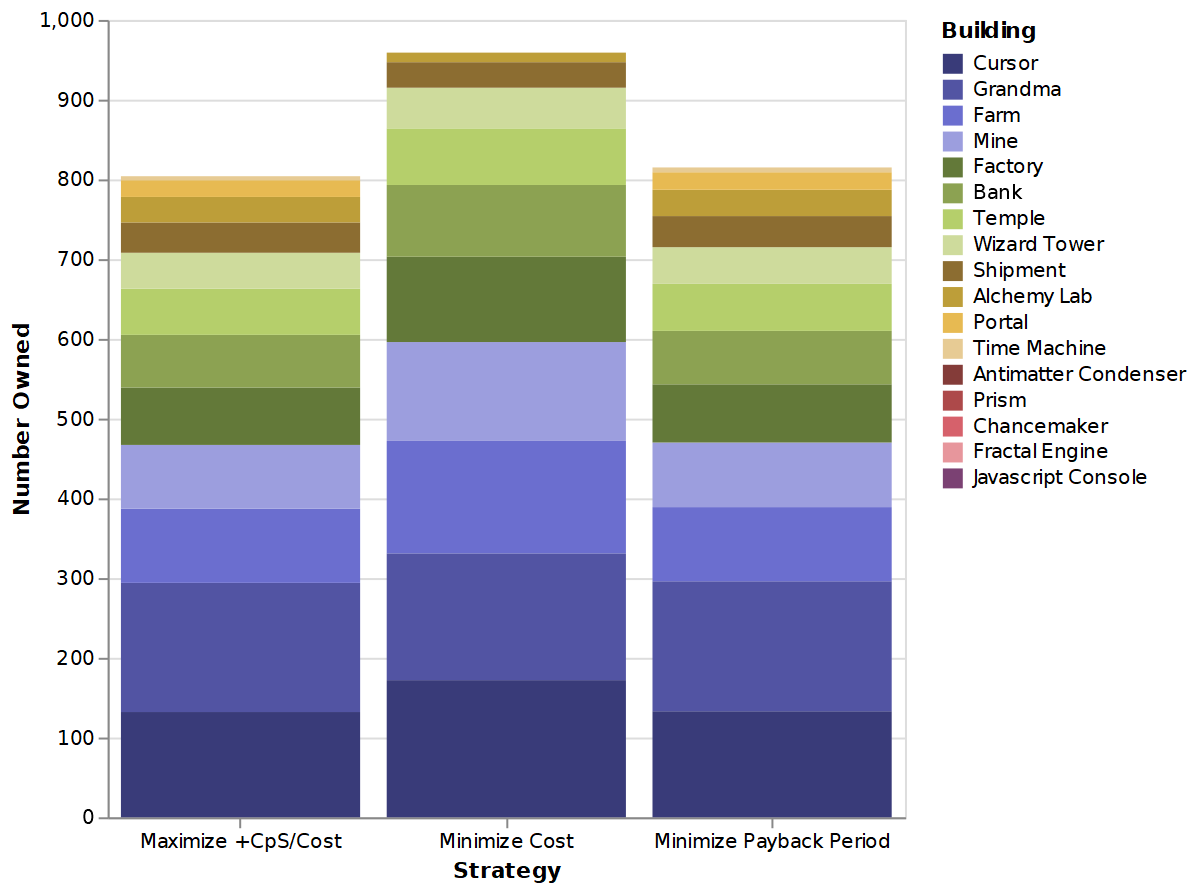

Minimize Payback Period did the best, closely followed by Maximize +CpS/Cost; Minimize Cost trailed far behind. This was surprising at first, but it makes sense in hindsight. Always buying the cheapest item is a hilariously greedy strategy; you’ll end up buying loads of low-tier buildings before you get any upgrades or higher-tier buildings. This is supported by the breakdown of what buildings each strategy ended up with:

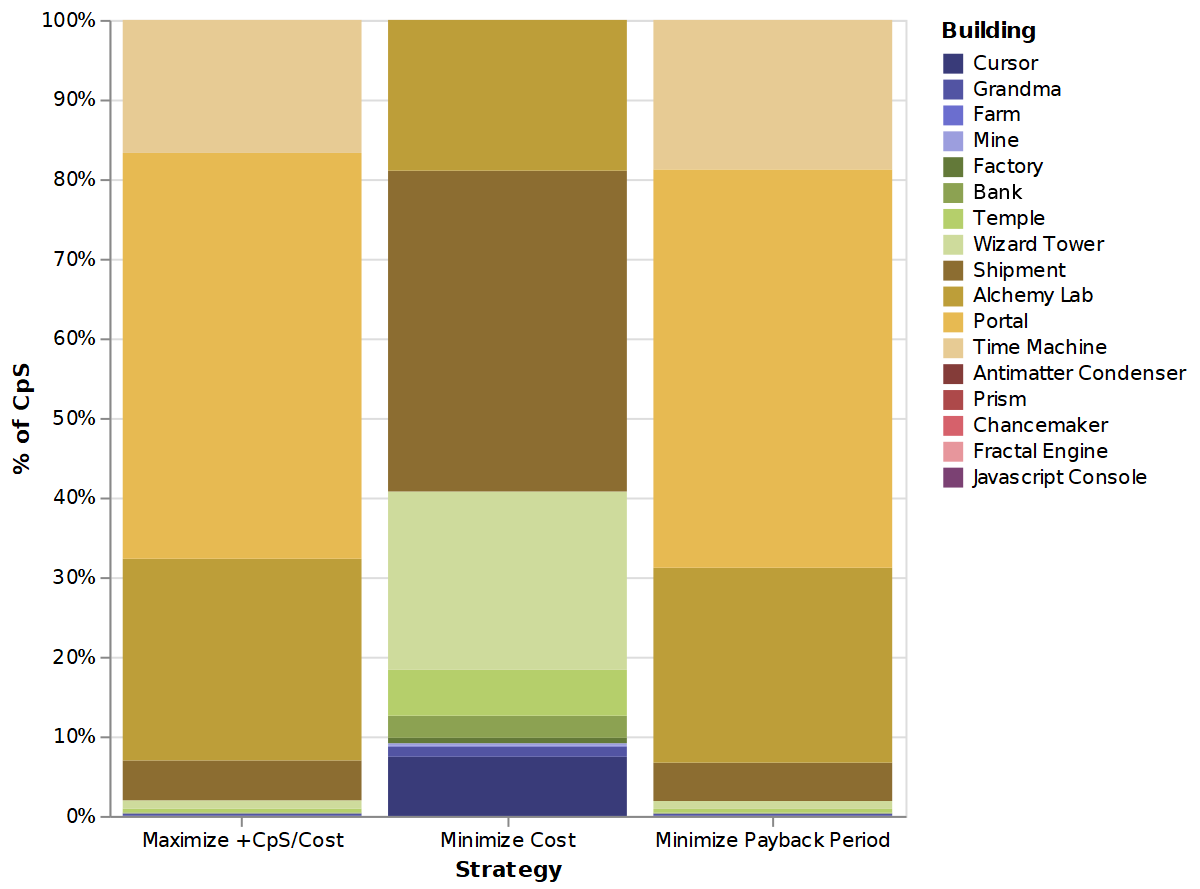

Minimize Cost ends up with more buildings than the other two strategies, but those buildings are worse on average. The breakdown of where these strategies get their cookies is similarly enlightening:

The effective strategies rely on the higher tier of buildings; Minimize Cost gets a surprising amount of mileage from their cursors.

As for Minimize Payback Period and Maximize +CpS/Cost performing similarly, that’s easily explained by them being very similar strategies. Maximizing \(\frac{\Delta \text{CpS}}{\text{Cost}}\) is the same thing as minimizing the time it takes for that item to pay for itself. (Apparently considering how long it takes to afford something is only a slight improvement.)

Other Experiments

After finding this optimal strategy, I decided to run some other experiments with my simulator to see what would happen. All the simulations below use Minimize Payback Period for their strategy.

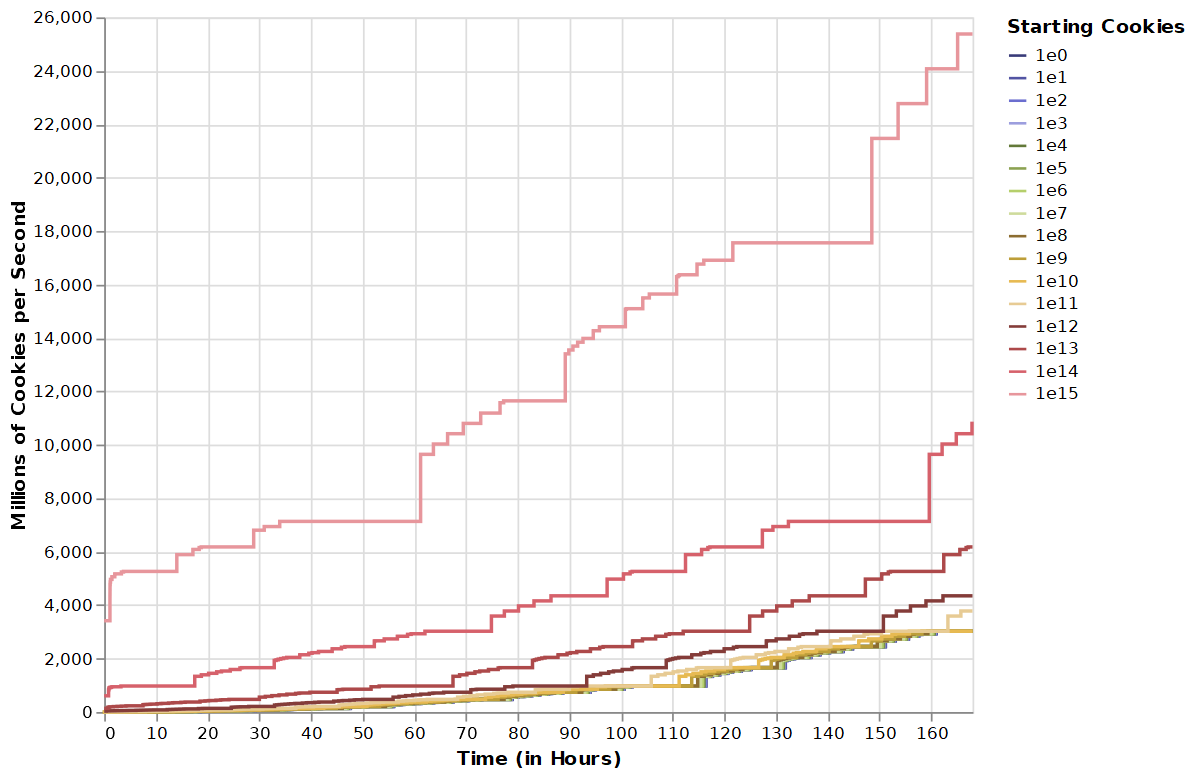

Head Starts

Exponential growth has a tendency to amplify head starts. This is a game all about exponential growth; how much of a head start does it take to make a noticeable difference?

This is basically exactly what we’d expect. Starting with cookies lets you buy more items at the start of the game, skipping the time you’d have to wait for them.

Clicking

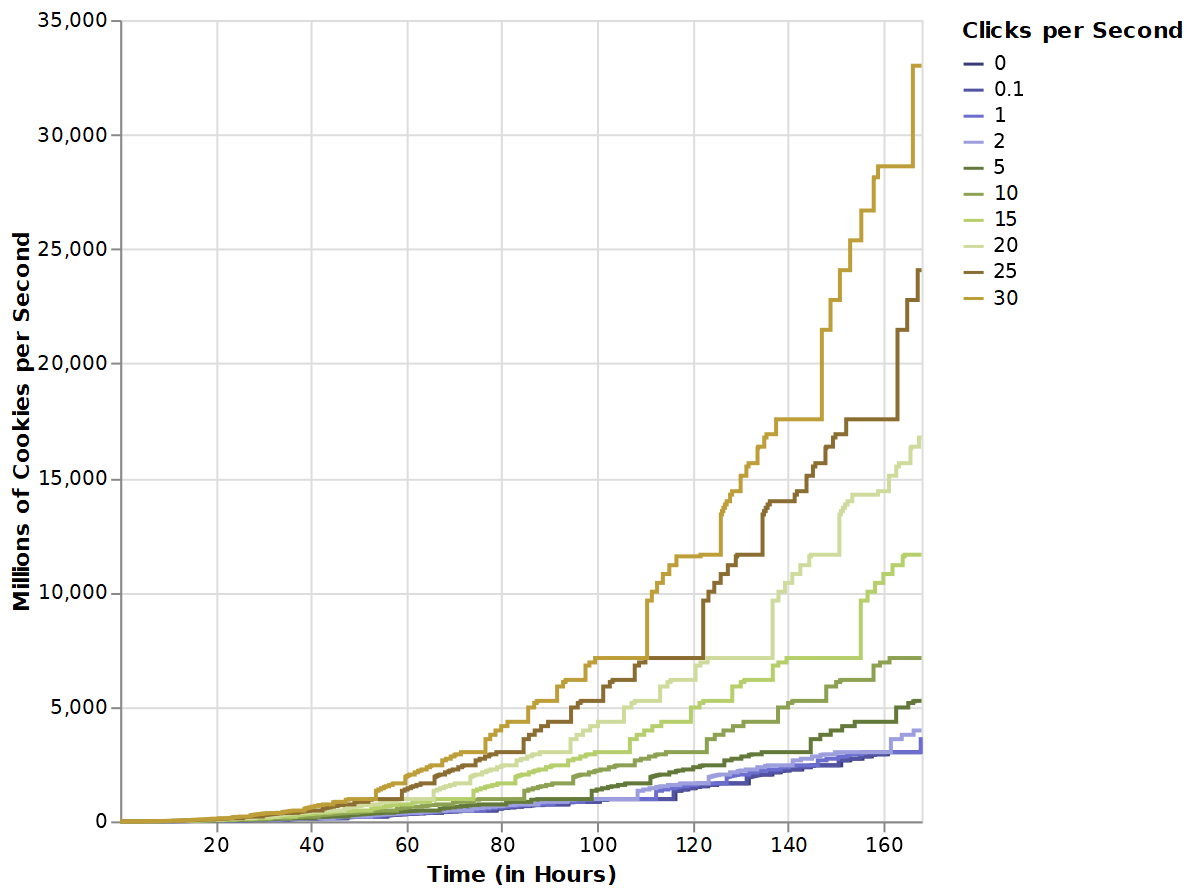

The simulation previously hadn’t considered clicking. It was pretty simple to implement, though, and once I had added the relevant upgrades I ran some tests with different clicking rates. I assume most players click very rarely, so the bottom of the scale is 0.1 clicks per second. The top of the scale is 30 clicks per second; the game’s framerate is at most 30 frames per second, and most sources I’ve found say the game can only register one click every frame.

(Note that graphed CpS does not count cookies earned from clicking.)

This graph isn’t much of a surprise either. The faster you earn cookies, the faster you can buy new upgrades. Still, I think it’s interesting how wide a gulf there is between not clicking and clicking as quickly as possible. I’d always thought clicking became obsolete pretty quickly, but this graph shows that’s not the case.

Conclusion

This was a very silly endeavor, but at least it was an educational silly endeavor. Learning how to make graphs from the command line served this experiment well, and it’ll be a useful skill to have for future ones. In the end, it’s fun putting way too much effort into something trivial. Hopefully I’ll be able to use my experience here to optimize something useful someday.